In terms of secure communications in tactical environments, the United States has held a distinct technological advantage over our adversaries in recent history. Over the past 20 years in Iraq and Afghanistan, our tactical communications have never truly been challenged. America’s military has very rarely had to operate in a contested environment, which in some ways, has bred a level of complacency when it comes to our ease of communicating.

In terms of secure communications in tactical environments, the United States has held a distinct technological advantage over our adversaries in recent history. Over the past 20 years in Iraq and Afghanistan, our tactical communications have never truly been challenged. America’s military has very rarely had to operate in a contested environment, which in some ways, has bred a level of complacency when it comes to our ease of communicating.

Complacent tactical communications practices

From recent experience as a JTAC (Joint Terminal Attack Controller) in Afghanistan, I can attest that after decades of technological superiority over adversaries in Iraq and Afghanistan, the ability to communicate on the battlefield is treated as a constant rather than a variable. This thinking is not tolerable for the next fight with a near-peer adversary.

From recent experience as a JTAC (Joint Terminal Attack Controller) in Afghanistan, I can attest that after decades of technological superiority over adversaries in Iraq and Afghanistan, the ability to communicate on the battlefield is treated as a constant rather than a variable. This thinking is not tolerable for the next fight with a near-peer adversary.

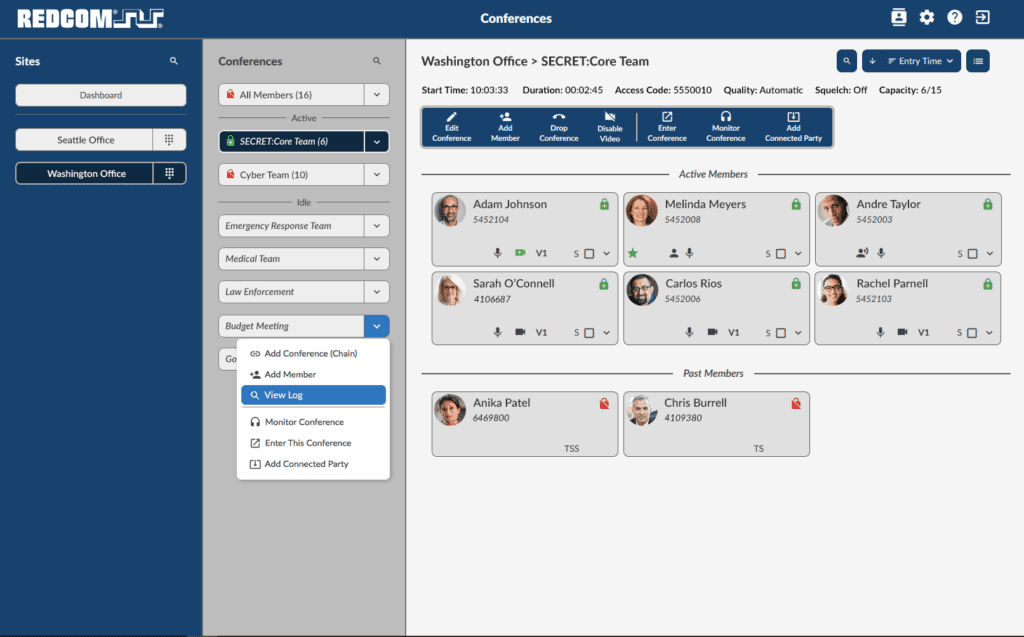

Today, you will be hard-pressed to find a GFC (Ground Force Commander) that is not in constant contact with higher command echelons. For an operation to receive the green light, it has become a minimum force requirement to have at least one air asset in direct support for communication relay. Even if said asset is an unarmed ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) platform, this component is required so command personnel can be tied into ground activities. Air support provides command with the ability to monitor ISR feeds from a dislocated operations center and relay updates to the ground via aircraft to a JTAC to the GFC. Relying on a low-flying aircraft orbiting directly overhead to keep C2 (Command and Control) tied into the battlefield is not sustainable. When looking into the next fight, and the defense technology of our adversary, we need to step up our game.

Critical combat communications

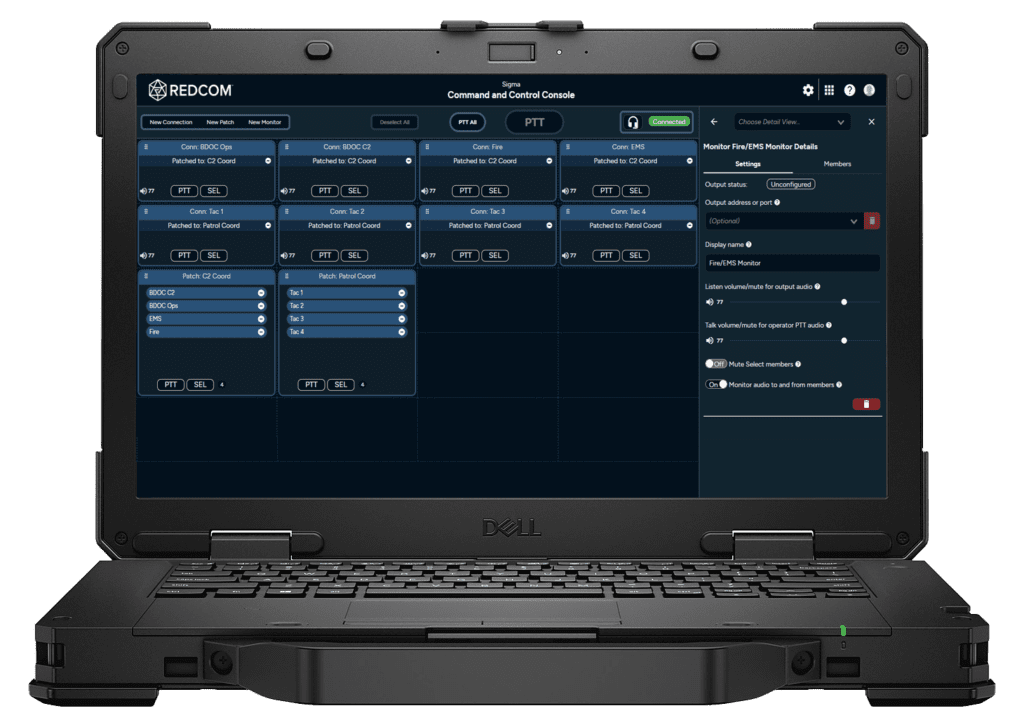

While the current standard of battlefield communications is unsustainable in the next fight, that’s not to say tactical communications won’t be critical to the success of future operations. In the combat zone, the flow of vital information depends on the ability to communicate via voice across platforms. Currently, for a GFC to ensure the safety of his team, make informed decisions, and provide direction and maneuver instructions, he must use LOS (Line of Sight) to communicate. In the event a team is pinned down, unable to break contact, or gain fire superiority, a JTAC needs uninterrupted two-way comms with an aircraft to execute air-to-ground engagement.

American lives rely on this communication being unimpeded and in constant operation. But what happens when one of those systems fail? Due to our current opponent’s inferior technological capabilities, it is only in rare cases today that we see devices intentionally disrupted. It’s more likely that the issue can be traced back to a self-induced error (e.g.: SATCOM being disrupted by our own jamming devices or incorrect keys being loaded in a radio). Even when a communication error takes place, we can still transmit in the clear as the last resort without much concern that the transmission will be intercepted and manipulated by our enemy. However, this backup will not be available in a near-peer fight where a breakdown in communication will likely be the result of electronic attack capabilities. The notion of utilizing air support to relay comms is also unlikely in the next fight, as the adversary will possess sophisticated anti-air capabilities.

American lives rely on this communication being unimpeded and in constant operation. But what happens when one of those systems fail? Due to our current opponent’s inferior technological capabilities, it is only in rare cases today that we see devices intentionally disrupted. It’s more likely that the issue can be traced back to a self-induced error (e.g.: SATCOM being disrupted by our own jamming devices or incorrect keys being loaded in a radio). Even when a communication error takes place, we can still transmit in the clear as the last resort without much concern that the transmission will be intercepted and manipulated by our enemy. However, this backup will not be available in a near-peer fight where a breakdown in communication will likely be the result of electronic attack capabilities. The notion of utilizing air support to relay comms is also unlikely in the next fight, as the adversary will possess sophisticated anti-air capabilities.

Preparing for the next fight

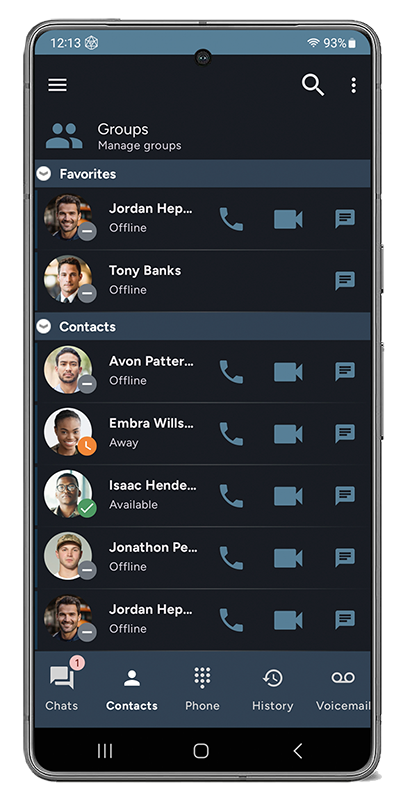

The demand for reliable and secure communication solutions that can be scaled down and carried in ruck has never been more prudent. Design focusing on Low SWaP (Size, Weight, and Power) and ease of use need to be geared towards the sled dogs who will ultimately be relying on these systems under fire. Those designing these communication systems must keep this in mind, and always think ahead to the next fight when developing solutions critical to the success and safety of our men and women fighting on the front lines.